|

The Society of Folk Dance Historians (SFDH)

A Dancer's Paradise

[

Home |

About |

Encyclopedia | CLICK AN IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

|

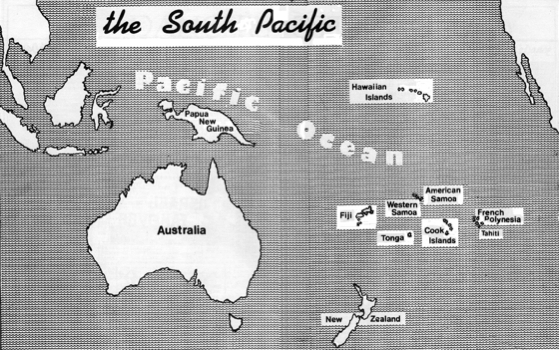

When it comes to telling about the South Pacific Islands, I never know where to begin. The islands are a feast for the senses.

The sights are magnificent: the sparkling, clear Pacific waters reflect the infinite blue of the skies; the miles of coconut plantations; the abundance of untamed, lush, green tropical growth enhanced by flowers that bloom in every hue of the rainbow; the brown-skinned islanders, with their special smiles.

Maybe I should tell you about the sounds of the Islands: the exciting pulse of the pahu and toere drums of Tahiti; Tongan women pounding out tapa; the crowing of dozens of roosters at dawn in a Samoan village; a coconut falling onto the roof of a Samoan dwelling; the swishing of palm fronds in a balmy evening breeze; soft, mellow voices singing to ukeleles and guitars; the gentle slap of the waves on the shore at night on Toberua Island, Fiji.

I could try to describe the almost intoxicating fragrances of the flowers and plants, but words are inadequate. One is frequently aware of the pleasantly overwhelming scent of Plumeria blossoms almost everywhere.

Let's not ignore the mouth-watering tastes of the islands: the French Polynesian cuisine of Tahiti that combines sauces with freshly-caught sea delicacies; the Samoan sua esi (papaya and coconut cream) for breakfast; or their palusami (taro leaves steamed in coconut milk). Then there are the Fijian tea cakes and their island's curried delectables influenced by the Indian culture there. Finally, all over the islands are fresh bananas, papayas, mangoes, and pineapples.

I could go on and on, but you could read all of this in a travel brochure (which I would gladly write!). The travel literature does not exaggerate.

The intent of this article is to describe the dances I was fortunate enough to observe and, in some cases, to learn to do. I traveled with a specially created tour group of people who wanted to study Polynesian dance. Our tour leader was an American, but an expert on South Seas cultures.

Our journey began in Papeete (pah-pah-yeh-tey), Tahiti. In the evenings, we were royally entertained by a variety of dance troupes, some of whom were recent prize winners in the annual Bastille Day Tahiti Fete.

The vahines (vah-hee-neys, women) wore a matching bra top and pareo (pah-rey-oh), Tahitian floral print fabric wrapped around the hips. The plumeria leis around their necks matched the leis they wore on their heads and around their hips. The tanes (tah-neys, men) also wore pareos and floral head pieces but their leis were of leaves.

The dancers were performing the Aparima (ah-pah-ree-mah), which is an action song to which both male and female dancers move their hands to act out a story. To keep the rhythm, the women sway or ami (ah-mee, rotate) their hips while the men usually tap one foot. Most of the story themes are about love or are scenarios of daily life. One Aparima, Te Manu Pukarua (the blackbird), tells about a fisherman who, after netting a big catch, decides to take a nap. As he snoozes, a mischievous little blackbird carries off the catch, fish by fish. The fisherman awakens just in time to see the little devil in the act and threatens to put the bird in a potato stew.

Enough of the tame stuff! The Tahitian dance that most readily comes to mind is the super-speed Otea (oh-tey-ah) which is done to the beat of drums. The drum "orchestra" consists of a pahu (pah-hoo, large drum), a toere (toh-eh-rey, log drum), and an empty gasoline can (a contemporary instrument, common to the islands). The dancers stand in rows facing the audience. The women, wearing skirts of stripped hibiscus bark and bras of coconut shells, sway very fast. The skirts undulate and the hip tassels swirl wildly. In contrast, their torsos are so stationary that if you look from the waist up, it looks as if they are standing still. The feet are planted firmly on the ground (good dancers do not lift their heels). The women hold an i'i (tassels made of the same material as the skirt) in each hand. The i'i are usually flipped or waived.

The men have their own step. Basically they wave their knees together and apart while stepping in place or traveling from side to side. When dancing with a partner, they might do this step, moving around the women. The men also do little short kicks and jumps.

According to what I heard and read, I understand that the Otea was originally done as a flirtation. A young vahine would dance. If a tane was interested, he would join her. The movement was sensual; the eye contact was intense. Soon the happy couple would run off together to get better acquainted!

After saying Maururu (mow-roo-roo, thank you) to our Tahitian hosts, we bid farewell to Tahiti and said "Talofa (tah-loh-fah, hello) to Western Samoa.

After consecutive trips by prop plane and pickup trucks, we arrived at our next "home" on our tour, in Lalomalava Village, on Savai'i. Our host, Tavita, showed us to our sleeping quarters, a fale (fah-ley, dwelling with a mat-covered floor, mostly open walls and a roundish roof thatched with pandanus (pahn-dahn-ooz, palm leaves). The mattresses on the floor were covered with bright Samoan fabrics and separated so that the men could sleep on one side of the fale while the women were on the other side. At night, mosquito netting was hung from lines strung across the ceiling, forming protective tents around each bed.

We saw and did many interesting things while on Savai'i, the most outstanding being a one-day boat excursion to a small island called Manono, where we swam, snorkeled, ate fresh pineapple, and participated in an impromptu beach party which the local people started when they learned of our presence. The dancing and singing went on for several hours.

Later, back at the village, we were summoned by drums to the dining fale to eat and to observe and participate in Samoan customs and dance.

First was the Kava Ceremony, a welcoming ritual. Kava is a drink made from water and ground pepper root. The person who makes the kava is usually a Taupou (toh-poh, a chief's daughter) or other woman of high rank. She wears a costume of tapa (tah-pah, cloth of mulberry bark and decorated with natural dyes) wrapped around her body from under the arms to below the knees. On her head is a crown decorated with feathers and what appears to be a blondish wig coming down from the sides. She also wears a necklace of boar teeth, a symbol of purity.

She sits cross-legged before a wooden bowl the size of an average kitchen sink, and passes a coconut fiber strainer through the combined liquid and pepper root to filter out the sediment. Every so often she hands the strainer to a young man who goes out behind the fale and shakes out the residue, then places the strainer back into her waiting palm. After the filtering process, the kava maker stirs the mixture. When the kava is ready, she holds her palms, face down, above the bowl. The chief makes a welcoming speech. Then, the taupou dips half a coconut shell into the kava. She hands it to a man, the server. He faces the person he is about to serve, then walks quickly and directly to him. The recipient takes the shell, spills out a little kava, says "Manuia tato aso" (mahn-wee-ah tah-toh ah-soh, a toast meaning good fortune), and drinks the kava. The serving continues in this manner. The men are served according to their importance in the village. The women are not served. This is "fa'a Samoa," the Samoan way. Although I did not taste the kava, I did later try a similar Fijian drink, yaquona, which looks and tastes like dishwater and works like novocaine. It numbs the mouth and is supposed to produce a euphoria, although it is not a narcotic. Though my mouth got numb, I felt no other sensation, but some others said that they did.

After the Kava Ceremony, the entertainment began. First the men, dressed in formal black lava lavas (lah-vah lah-vahs, wrap arounds), performed a Sa Sa. The Sa Sa is a seated dance done to the beat of the pate (pah-tay) or gasoline can. To begin the dance, all sit cross-legged. There is a drum roll and the leader shouts "Talolo!" (tah-loh-loh, bend over). The dancers lean forward from the waist while the leader walks around with mock sternness to make sure everyone is complying. In this instance he even carried and axe as if to behead anyone who was misbehaving. The Samoans thought this was very funny. At first, we were not quite sure . . .

Though exaggerated for humor, the leader's actions made sense. The majority of Samoan dances demonstrate the Samoan value of doing things for the good of the group rather than drawing attention to one's own expertise. The Sa Sa, which looks like a precision drill, is a good example of this concept.

Back to the dance description. After the leader is satisfied that all are at attention, he yells "Nofo!" (noh-foh) and all straighten up again. The drums begin a fast, steady beat: and-a-one, and-a-two, etc. The dancers, still seated, begin bouncing their knees vigorously while simultaneously slapping them. Then, keeping the rhythm, they clap twice, one pati (pah-tee, a flat-handed clap), and one po (poh, a cupped hand clap), and shout the Samoan greeting, "Talofa!" (tah-loh-fah).

As the dance progresses, our host explained that they were acting out the making of kava, a common dance theme. We could recognize that the dancers' hands were doing the motions for this task. They knew when to stop one motion and begin the next, because there was a slight change in the drum beat to signal them. Then, the regular beat would resume. Each new movement would continue until they heard the changing signal again. To finish the dance, the performers stood up and ran in place, continuing some of the clapping and slapping. They exited, running and yelling "Ch'hoo!" (ch-hoo, their equivalent of "hopa!").

The women, dressed in their puletasis (pooh-lay-tah-see, matching lava lava and over-blouse) with feather belts around their waists, showed another type of dance, the Maulu'ulu. This is a standing dance in which the dancers interpret the content of a song with their hands, while the heels of the feet move apart and together. This movement is called the siva (see-vah) step. One of the dances we saw was called Pea E Siva. The song says that a Samoan woman is very special when she dances.

Aside from being a dance step, the Siva, itself, is a dance. It's uniqueness lies in the fact that it is a dance which expresses one's individual style rather than expressing the importance of the group effort. The Siva, done by both men and women, is much like the Ma'ulu'ulu because one does it to a song or to instrumental music rather than to a drum beat. The Siva, however, is more of a freestyle interpretation and is a solo dance, even though several may be doing it at once.

Men and women do the same foot movement, that is, the Siva step. The basic hand movement is a flick of the fingers. The women do this gracefully, while the men have a more staccato movement. Traditionally, when a young girl does the Siva, several men will join her. They dance around her and make a lot of noise, trying to fluster her. She is supposed to be obvious about ignoring them and continue dancing. This is to demonstrate her growing poise.

All to soon, we had to say "Tofa, Samoa," and "Fa'afetai (thank you), and head for Viti Levu, the largest of the Fijian isles.

The first Fijian expression I learned was "Bula" (mboo-lah, the greeting word). The second was "Lakotani, vuaka!" (lah-koh-tah-nee, voo-ah-kah). You see, we had to share our bure (boo-ray, Fijian dwelling) with a hen and a pig. We didn't mind the occasional cackles of the hen, but the pig frequently ambled through the bure, walking all over our sleeping bags and luggage. So, we asked some kids to say, "Get out, pig!" They gleefully taught us "Lakotani, vuaka!" You'll have a hard time finding that one in the phrase books!

Soon after dark, some of these children came to our bure, bearing flashlights, to take us to the Meke (may-kay, dance). The Meke was held in the community hall. There are separate men's and women's Mekes. In this particular village (near Suva), the women's Mekes were done only by the very oldest women. I asked why and learned that the younger women must wait to be invited to learn and perform the Meke. Although the answer was no more specific than that, I had the impression that the girls had to reach maturity or responsibility to be asked.

A Meke, similar to many Polynesian dances, is primarily a hand dance. Often, the women's Meke is performed seated, with the knees bouncing very slightly (not wildly, like the Samoans) to the rhythm of the guitars, ukeleles, lali (lah-lee, log drum), and the derua (ndee-roo-ah, a hollowed out bamboo pole, one end of which is struck on the ground). Each verse of the Meke is usually begun with clapping, followed by the appropriate hand gestures. These motions are very simple with little embellishment except for an occasional turning of the hands or rolling of the fingers. Generally, the movement begins close to the body and moves outward. For instance, the smelling of a flower would be shown by first placing the hand near the nose, then moving it out and away from the nose. To emphasize the moving away, the dancers lean their torsos in the same direction in which the arm is extended.

It was difficult to learn the meanings of the traditional Mekes, The singing that accompanies the orchestra is done in a mumbling monotone that even many of the Figians do not understand. Only the performers know the meaning. The villagers, however, taught us a simple contemporary Meke called Makosoi, about a flower that has a pleasant scent and produces an oil that feels good on the skin.

We did not see a men's Meke until the next day. It was our good fortune to be on hand for the Festival of the Pines. A year ago, they had begun a pine forest with some imported Australian pines and now they were celebrating their first anniversary. The festivities, all outdoors, included some games such as a tree-stump chopping contest and a tug of war. Since there were other villages in attendance, there also was a dance competition.

Most of the costumes here fit into a general pattern. The women wore long skirts of tapa or fabric with over-skirts of similar material. Many of the women wore a short-sleeved peasant blouse, though some of the tapa costumes covered most of the body and didn't require a blouse. The leis were made of brightly colored straw-like material. The men had several kinds of costumes. The simplest was a sulu (soo-loo, a bright print fabric wrapped around the waist and reaching to the knees). For war dances, they wore a multicolored hibiscus skirt (similar to the Tahitian's) and carried spears and shields.

The women did several standing Mekes that day. One type looked something like a line dance. During parts of it, they used a shoulder hold and did some step-togethers from side to side. A very interesting Meke was the Fan Dance. They used a small fan decorated with feathers and moved it about. Sometimes they shook, wiggled, waved, or clapped with it.

The men performed a spear Meke. They entered in two opposing lines, one from the right and one from the left. They pointed their spears at each other. Their postures were very aggressive: knees bent in a semi-squat position, bodies leaning slightly forward from the waist. The steps were mostly advancing or retreating flat-footed steps. Sometimes they would pause and point their spears toward the audience and make a war-like grimace. It was almost comical. At one point, the men laid down on the ground and shortly rose up again. One of the villagers told us that this was a hunting dance and that after the animal had been slain, his spirit rose up.

That evening we learned an easy dance that could be a part of an international folk dance repertoire. The name of the dance is Tuiboto (too-em-boh-toh). Dancers stand in a single file with their hands on the waist of the person in front of them. They begin with feet together. The basic step is a touch to the right with the right foot; then bring it back and step on it next to the left foot. Then the same step is done with the left foot. That's the dance. When you hear the shout "Ova!," you do an about face so you are facing the opposite direction and your hands are on the waist of the person who was in back of you before. The dance now continues in this new direction until the leader calls "Ova!" again.

The Tuiboto reminded several of us of our own American Bunny Hop, so we taught it to our Figian friends. If you ever happen to be in the Fijian village of Naivuruvuru, you might just see some Fijian villagers doing the Bunny Hop, to Fijian music!

This article does not begin to, or claim to, cover it all. I do hope it gives you some idea of the nature of Polynesian dance.

DOCUMENTS

Used with permission of the author.

Printed in Folk Dance Scene, November 1985.

This page © 2018 by Ron Houston.

Please do not copy any part of this page without including this copyright notice.

Please do not copy small portions out of context.

Please do not copy large portions without permission from Ron Houston.